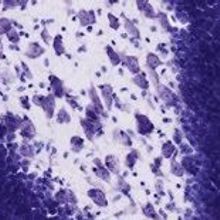

Horizontal section through the mouse hippocampusWIKIMEDIA, BRAINMAPS.ORG

Horizontal section through the mouse hippocampusWIKIMEDIA, BRAINMAPS.ORG

Traumatic memories are some of the most tenacious and long-lived. The more recent the memory, the more amenable it is to reconsolidation, where it is recalled and can then be modified to become less fearful. Researchers from MIT have now shown that a DNA modification that is controlled in part by the enzyme histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) helps make recent memories more prone to reconsolidation. The work was published last week (January 16) in Cell.

The researchers initially trained mice to fear a cage or a tone by administering a foot shock in the cage or while the tone was played. They then returned the mice to the cage or played the tone, so the animals would recall the fearful memory, tried to extinguish the memory by exposing the mice to the cue consecutively over three days, and compared the...

“We showed that new fear memories can be modified or extinguished through exposure therapy, but for old memories, the exposure-based therapy is not very effective,” coauthor Li-Huei Tsai told The Los Angeles Times.

The team then showed that after recall in mice with the recent fearful memory, histone 3—one of the proteins around which DNA is packaged—was more acetylated in the hippocampus compared to both naïve mice and to mice in which the memory was more remote. They found that HDAC2, which is responsible for removing acetyl groups from histones, is modified by nitrosylation and dissociated from chromatin during recall of early memories, allowing memories to be modified. When the researchers tried drugs that blocked HDAC2 activity in mice with more remote memories, the mice were better able to reconsolidate fearful memories. They also demonstrated that epigenetic changes that were the result of restricted HDAC2 activity lead to transcription-dependent neuronal plasticity.

“Specific nitrosylation of HDAC2 obviously affects several genes important for reconsolidation updates—apparently as memories age, this mechanism fails,” Jelena Radulovic of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois, who was not involved in the research, told ScienceNOW.

Some HDAC2 inhibitors are already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of cancer, so these drugs could represent possible treatment avenues for conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder. “I hope this will convince people to seriously think about taking this into clinical trials and seeing how well it works,” Tsai said in a statement.

Interested in reading more?