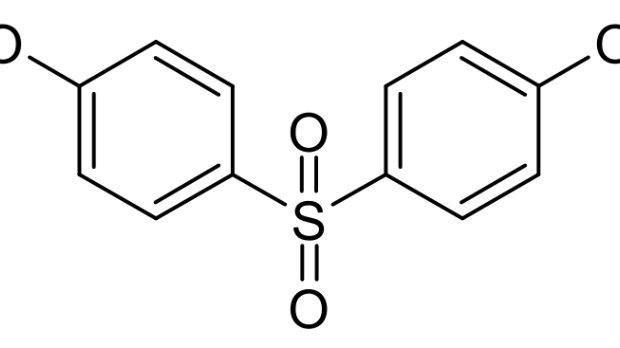

Bisphenol SWIKIMEDIA, ROLAND1952Bisphenol A (BPA), a plastics ingredient, is generally recognized as an endocrine disruptor, and concerns over its potential impact on human health have prompted manufacturers to eliminate it from some consumer products. A few nations have even implemented partial bans on how the chemical can be used, and last year, France went to far as to ban BPA from food packaging altogether. Yet “BPA-free” does not necessarily mean free of all bisphenols—and as a pair of recent studies show, substitutes for BPA affect cells and animals in much the same ways.

Bisphenol SWIKIMEDIA, ROLAND1952Bisphenol A (BPA), a plastics ingredient, is generally recognized as an endocrine disruptor, and concerns over its potential impact on human health have prompted manufacturers to eliminate it from some consumer products. A few nations have even implemented partial bans on how the chemical can be used, and last year, France went to far as to ban BPA from food packaging altogether. Yet “BPA-free” does not necessarily mean free of all bisphenols—and as a pair of recent studies show, substitutes for BPA affect cells and animals in much the same ways.

It’s hard to get a handle on all the chemicals present in plastic products, no less so in items labeled BPA-free. The presumption is that at least some BPA-free items contain a BPA analog—such as bisphenol S or F (BPS, BPF)—as a replacement, and a 2012 study including more than 300 volunteers found BPS in...

But compared to BPA, there have been far fewer studies on related bisphenols, prompting a number of groups to compare the cellular and physiological effects of these chemicals. Most recently, Pascal Coumailleau of INSERM’s Research Institute for Environmental and Occupational Health and the University of Rennes in France and colleagues measured the effects of four bisphenols on the brains of zebrafish.

Exposing the animals to higher concentrations of these chemicals than humans would typically encounter, the team found that three of four BPA analogs—BPS, BPF, and BPAF—are estrogenic, causing an upregulation in the brain of the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens—such as testosterone—to estrogens. Overall, these chemicals are similar to BPA in their effects on zebrafish, Coumailleau, whose team published its work in Frontiers in Neuroscience last month (March 24), told The Scientist.

Coumailleau’s group did not follow the fish’s development long term but, he said, “if you affect the right balance of these hormones, we can speculate there will be some problems,” such as during the development of sex differences in the brain. Boosting estrogen levels, for instance, can blunt the normal masculinization of the brain that occurs in males during development, he said.

“What the [paper] nicely shows is that not only BPA but a lot of BPA analogs really do have estrogenic activity,” said Deborah Kurrasch, a neuroscientist at the University of Calgary who has also examined the activity of BPS in zebrafish but was not involved in the study. “This suggests there isn’t a safe bisphenol.”

Last year, Kurrasch and colleagues reported that exposure to low doses of BPA or BPS cause larval zebrafish cells to mature into neurons prematurely. They also found that treated fish were more likely to display hyperactivity later on. “We did show there is some consequence to this precocious neurogenesis,” she said.

In December 2015, Nancy Wayne, who studies reproduction at the University of California, Los Angeles, and her collaborators reported the effects of BPS and BPA on the zebrafish reproductive system. And the team found similar results: exposure to both chemicals resulted in greater numbers of reproductive neurons and an upregulation of reproduction-related genes, the researchers reported in Endocrinology. “If you look at the structures of BPA and BPS, they’re so similar that it would be surprising if there weren’t similar effects for everything you look at,” Wayne said.

And the effects don’t stop at the neuroendocrine system.

Another study published last month (March 22) in Endocrinology looked instead at the influence of BPS on fat production. Exposing cell precursors extracted from women to BPA and BPS, Ella Atlas of Health Canada and colleagues found that the chemicals led the cells to accumulate lipids and increase the level of transcripts indicative of differentiation into fat cells. “They both seem to increase adipogenesis,” Atlas told The Scientist, with BPS being more potent than BPA.

Atlas’s experiments suggested that BPS acts through a fatty acid receptor called PPARγ, which controls fat cell development. A number of environmental chemicals suspected of being “obesogens,” meaning they may cause weight gain, also activate PPARγ.

“We have a problem of obesity in this country and it’s been blamed entirely on a change in our level of physical activity and our diet, and it certainly is believable,” said Wayne. “But there can be in addition to that another culprit. And another culprit can be various endocrine-disrupting chemicals that are altering metabolism.”

Atlas said it’s impossible to extrapolate from her study how BPS affects people, and whether it causes fat production in humans in vivo. “It’s basically raising a flag that it may be a problem,” she said.

Anne Marie Vinggaard of the National Food Institute at the Technical University of Denmark has also looked at lipid accumulation in fat cells, finding that BPS and BPA act similarly. “So far we think the data are indicating that we should not substitute BPA with BPS,” she said.

Yet BPA continues to be the prime focus of research and policy efforts to protect consumers while its analogs fly under the radar. Last month, the European Union announced that it is considering new restrictions on BPA in food packaging—specifically, how much of the chemical would be allowed to migrate from containers to food. But there is no mention of BPS, BPF, or any other similar substance that may be present.

“Most people think, ‘BPA-free, oh, it’s safe,’” said Wayne. “What does that mean? If they’re not using BPA, what are they using? And is it safer?”

J. Cano-Nicolau et al., “Estrogenic effects of several BPA analogs in the developing zebrafish brain,” Frontiers in Neuroscience, doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00112, 2016.

J.G. Boucher et al., “Bisphenol S induces adipogenesis in primary human preadipocytes from female donors,” Endocrinology, 157:1397–1407, 2016.

W. Qiu et al., “Actions of bisphenol A and bisphenol S on the reproductive neuroendocrine system during early development in zebrafish,” Endocrinology, 157:636-47, 2016.

Interested in reading more?