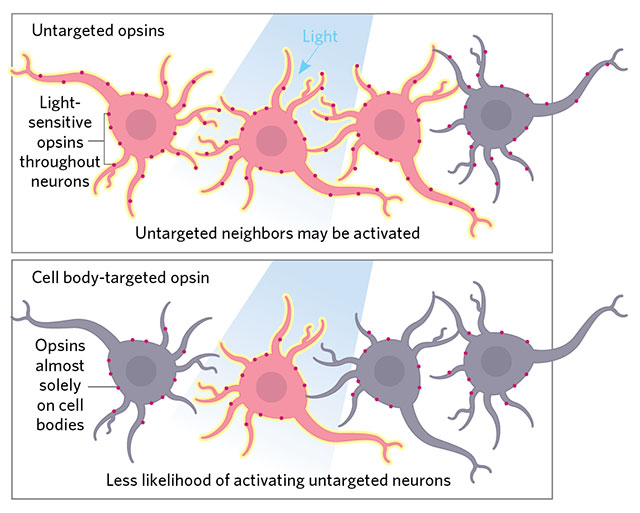

ON TARGET: Precision illumination techniques target light to individual neuronal cell bodies, but neighboring cells may be activated if their dendrites or axons lie nearby. Unlike regular opsins, which are distributed throughout the entire neuron, cell body–localized opsins, such as those described by Christopher Baker of the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience (eLife, 5:e14193, 2016) and now Edward Boyden’s team (Nat Neurosci, 20:1796–1806, 2017), prevent such stray activation. Boyden and his collaborators also use a more responsive channelrhodopsin for high-speed firing.© LUCY READING-IKKANDA

ON TARGET: Precision illumination techniques target light to individual neuronal cell bodies, but neighboring cells may be activated if their dendrites or axons lie nearby. Unlike regular opsins, which are distributed throughout the entire neuron, cell body–localized opsins, such as those described by Christopher Baker of the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience (eLife, 5:e14193, 2016) and now Edward Boyden’s team (Nat Neurosci, 20:1796–1806, 2017), prevent such stray activation. Boyden and his collaborators also use a more responsive channelrhodopsin for high-speed firing.© LUCY READING-IKKANDA

When optogenetics burst onto the scene a little over a decade ago, it added a powerful tool to neuroscientists’ arsenal. Instead of merely correlating recorded brain activity with behaviors, researchers could control the cell types of their choosing to produce specific outcomes. Light-sensitive ion channels (opsins) inserted into the cells allow neuronal activity to be controlled by the flick of...

Nevertheless, MIT’s Edward Boyden says more precision is needed. Previous approaches achieved temporal resolution in the tens of milliseconds, making them a somewhat blunt instrument for controlling neurons’ millisecond-fast firings. In addition, most optogenetics experiments have involved “activation or silencing of a whole set of neurons,” he says. “But the problem is the brain doesn’t work that way.” When a cell is performing a given function—initiating a muscle movement, recalling a memory—“neighboring neurons can be doing completely different things,” Boyden explains. “So there is a quest now to do single-cell optogenetics.”

Illumination techniques such as two-photon excitation with computer-generated holography (a way to precisely sculpt light in 3D) allow light to be focused tightly enough to hit one cell. But even so, Boyden says, if the targeted cell body lies close to the axons or dendrites of neighboring opsin-expressing cells, those will be activated too.

To avoid this, Boyden’s team fused a light-sensitive channelrhodopsin protein to a receptor that localizes to neuronal cell bodies, but not to axons and dendrites. With this approach, the likelihood of hitting just one cell with a targeted laser is far greater. “It eliminates the cross-talk of stimulating nearby cells,” says Robert Singer of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York and Janelia Research Campus in Virginia who was not involved with the work.

This opsin localization trick “is not intrinsically new,” Singer adds—other researchers have used a similar approach. “What is new is the combination of localization with a novel channelrhodopsin.” Boyden’s team used a recently discovered protein that requires less-lengthy and less-powerful light stimulation than other commonly used channelrhodopsins to activate neuronal firing. As a result, the firing was more immediate and predictable, increasing the temporal precision to a millisecond.

“Neurons in the brain fire with millisecond precision,” Boyden explains. Now there’s a single-cell optogenetic technique to match. (Nat Neurosci, 20:1796–1806, 2017)

![]()

| SINGLE-CELL OPTOGENETICS (reference) | OPSIN USED | FUSION PROTEIN | TWO-PHOTON STIMULATION | TEMPORAL PRECISION |

| C.A. Baker et al., eLife, 5:e14193, 2016 | Human channel- rhodopsin 2 (hChR2) | A domain of KV2.1 potassium channel, which localizes mainly to the cell body with a small degree of proximal dendrite localization | 180 mW per cell for 150 ms | 17 ms |

| O.A. Shemesh et al., Nat Neurosci, 20: 1796–1806, 2017 | High-photocurrent channelrhodopsin (CoChR) | N terminus of kainite receptor subunit 2 (KAV2), which localizes almost solely to the cell body of neurons | 30 mW per cell for 10 ms to 30 ms | Less than 1 ms |

Interested in reading more?