SOCIAL MONOGAMY: When individuals form social bonds and perform behaviors such as parenting in pairs, but don’t necessarily mate exclusively

EXTRA-PAIR PATERNITY: When a male fathers offspring outside of his social pair

GENETIC MONOGAMY: If a bonded pair only has offspring together, i.e., there is no extra-pair paternity

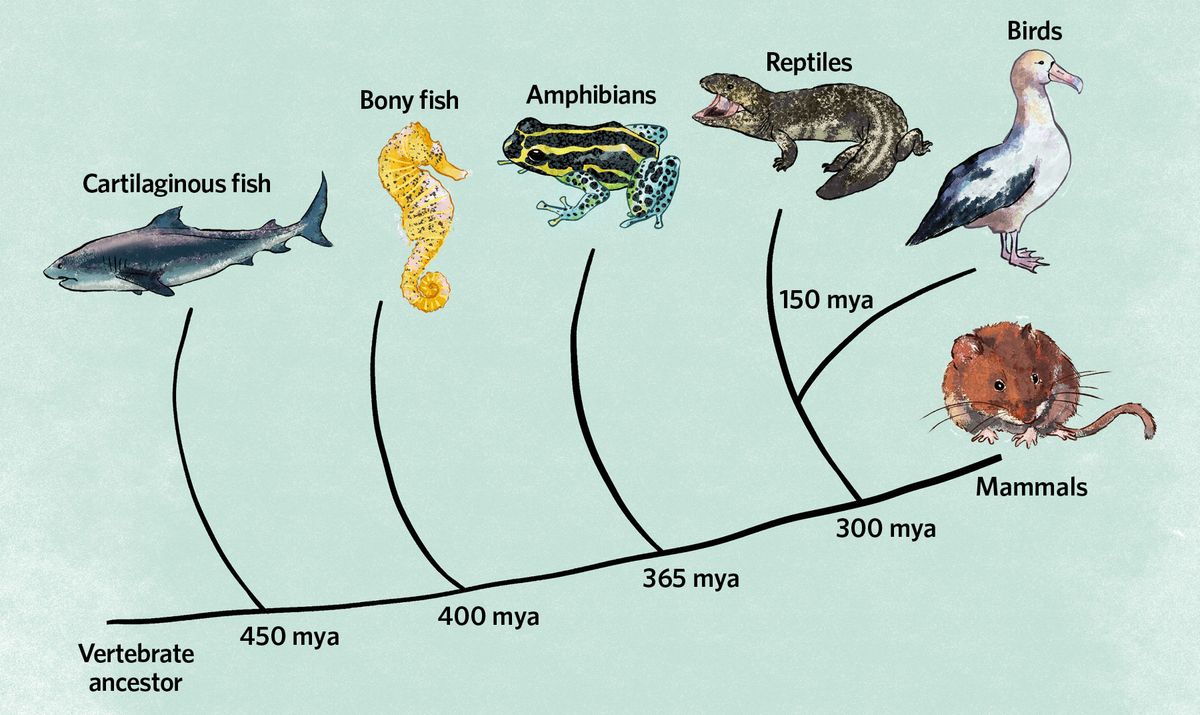

Cartilaginous fish

Although little is known about mating systems in sharks and other cartilaginous fishes, there is evidence that some species such as tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) could be genetically monogamous.

Bony fish

Most fish species are promiscuous, but some, such as seahorses (genus Hippocampus), are genetically and socially monogamous, with pairs mating and sharing parental care for most or all of their lifetimes.

Amphibians

Monogamy was thought to be absent from the amphibian clade, but in 2010 researchers published evidence of social and genetic monogamy in a Peruvian poison dart frog (Ranitomeya imitator).

Reptiles

Few reptiles are monogamous, but one exception is the Australian shingleback lizard (Tiliqua rugosa), which forms social relationships for 20 years or more—although around one-fifth of individuals have extra-pair relationships too.

Birds

Social monogamy is found in around 80–90 percent of bird species, although extra-pair mating is common. Albatrosses (family Diomedeidae) famously form strong social bonds that can last for decades.

Mammals

Fewer than 1 in 10 mammalian species practice some sort of monogamy. The socially monogamous prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster), which forms close bonds and even shows anxiety-like behaviors when separated from a partner, has become a well-studied model organism in research on monogamy, though they often mate with individuals other than their partner.

Read the full story.