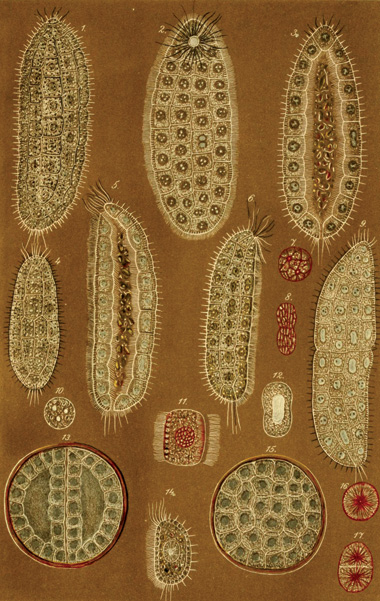

Two decades ago, Michael Schrödl, curator of the mollusk compilation at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology in Munich, Germany, attended a lecture on Salinella salve, a mysterious organism described as a single layer of cells, ciliated on both inner and outer surfaces and surrounding a central hollow sac open at both ends. Its body plan, which suggests a central digestive tract with a mouth and an anus, was unlike that of any known life-form. Composed of just one cell layer, Salinella seemed intermediate between single-celled organisms that perform all digestion inside the...

Was Salinella a missing link between protozoans and metazoans? A living relic of the transition from single-celled life to more complex forms with multiple cell layers? Schrödl was determined to find out. But there was one major problem—Salinella salve had been collected only once, by German biologist Johannes Frenzel, who claimed to have found it in the salt pans of Argentina in the late 19th century.

Sensing the opportunity for a scientific treasure-hunting adventure, Schrödl and a couple of friends set off for South America with only a vague, century-old description from Frenzel to guide them. “From our own pocket, but in the name of science, we bought a rusty car and went to Córdoba in Argentina,” Schrödl recounts. The first challenge Schrödl and his companions faced on their hunt was locating the source of the salt and soil from which Frenzel had reported culturing Salinella a century earlier. When they arrived at what they thought was the location where Frenzel had obtained the original Salinella sample, they found lush fields and mooing cows instead of salt pans and semidesert.

To make matters more complicated, during the course of the investigation Schrödl discovered that Frenzel had not actually collected the soil samples himself. A geologist friend had given them to him. Yet Schrödl figured that if Frenzel had indeed managed to coax Salinella to grow from dry dirt, then it could have survived as a wind-borne spore or cyst, and therefore it shouldn’t be restricted to one area. So he and his friends collected salt, sand, and earth from each salt lake they encountered across hundreds of miles of Argentina’s Córdoba Province.

According to Frenzel’s 1892 description in the journal Archiv für Naturgeschichte, he left his aquaria uncovered for months, exposing them to dirt, debris, and the occasional plant material. Schrödl attempted to follow Frenzel’s protocol for growing the elusive specimen—to no avail. “Many things were growing, but no trace of Salinella,” Schrödl says. Was Frenzel simply mistaken in his description? Schrödl thinks not, since Frenzel was a keen observer and a meticulous artist and would not have missed additional cell layers had Salinella indeed possessed them. Some have dismissed the Salinella mystery as scientific fraud, but Schrödl finds this hard to believe. Frenzel was a “serious scholar” who made valuable contributions to the fields of anatomy, protozoology, and ornithology, Schrödl says. And then there’s still the possibility that Salinella is “awaiting rediscovery as one of the most interesting creatures for scientific study ever,” Schrödl adds. “It was my dream to find it, and worth a try. Imagine the possibilities of modern molecular or microstructural research!”

Interested in reading more?