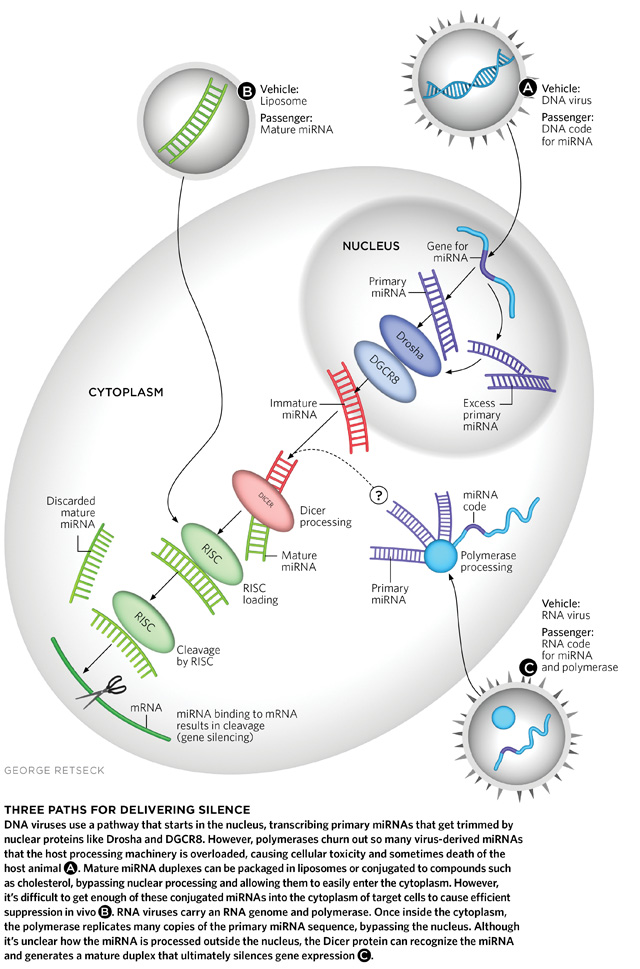

Since the discovery of RNA interference almost 15 years ago, researchers have tried to devise effective ways to get these short gene-silencing transcripts inside cells. But techniques for in vivo delivery have fallen short. For therapies that require long-term gene knockdown, DNA viruses that insert the microRNA (miRNA) genes into the target cell's genome were the best bet. But that approach produced large numbers of miRNAs, which overloaded the miRNA-processing proteins in the nucleus and resulted in cellular toxicity. For short-term therapies, mature miRNAs encapsulated in liposomes or conjugated to cholesterol were used, but they have been difficult to target to a specific cell type.

Benjamin tenOever, a virologist at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, tried an unusual work-around: cytoplasmic RNA viruses. Researchers had assumed that RNA viruses wouldn't do the trick because the miRNA transcript never enters the nucleus, and thus couldn't be processed...

The ideal application of such short-term knockdown is in cancer therapy, tenOever says, where modulation of oncogenic proteins is only necessary while the cancer cells live. (Mol Ther, doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.244, 2011.)  .

.

| STATS TALK | |||||

| COMPARING METHODS: | DETECTION | READABLE OUTPUT | IDEAL USE | SIGNAL TO BACKGROUND RATIO | NECESSITY FOR FOREIGN PROTEIN PRODUCTION? |

| DNA VIRUS | indefinite | 10,000s | very toxic | precise cell type | yes |

| SYNTHETIC miRNA | hours–days | 1-10s | nontoxic | organ specific | no |

| RNA VIRUS | hours–1 week | 100s–1000s | nontoxic | precise cell type | no |

Interested in reading more?