ANDRZEJ KRAUZE

ANDRZEJ KRAUZE

![]()

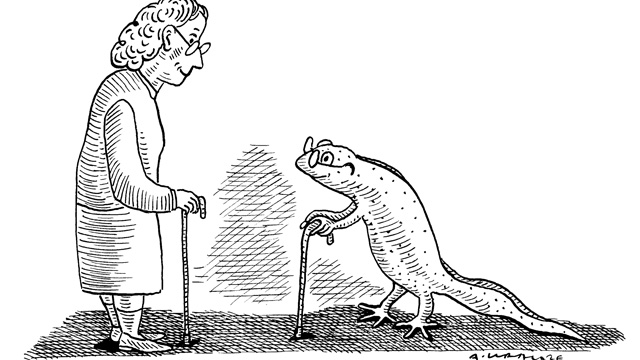

The humble newt has fascinated biologists for more than two hundred years. These amphibians, with their amazing and oft-cited ability to regrow lost body parts, have attracted the attention of regeneration researchers: cut off a newt’s tail or a leg, or remove a lens from its eye, and it grows back. However, whether newts can continue to do this throughout their lives, or lose the ability as they get older, has remained a mystery. Now, in an experiment spanning 16 years, Goro Eguchi of the Shokei Educational Institution, Japan, and Panagiotis Tsonis at the University of Dayton, Ohio, have discovered that newts can regenerate missing parts well into old age.

Newts do not thrive in laboratories over long periods of time; some species do not take to captivity at all, and for those that do, tanks have to be cleaned and water changed almost daily. So testing...

But Eguchi’s administrative duties kept him very busy, and he did not want to force his colleagues and technicians to take on extra work. On top of that, in 1996 he was appointed President of Kumamoto University, a post which did not allow him to run a laboratory. So instead, with the help of his wife Yukiko Eguchi (who died in 2007), he bred and raised captured Japanese fire-bellied newts (Cynops pyrrhogaster) at home. Yukiko’s skill with the newts kept them alive for sixteen years, during which time Tsonis and Eguchi removed lenses from the same animals 18 times. Eguchi estimates that the newts were about 14 years old when he captured them, making them 30 at the time the experiment was completed. While it is not easy to tell the age of wild newts, some can live for up to 50 years.

The Eguchis were also able to grow adult newts from fertilized eggs. Remarkably, when they compared lenses from these newts with the 17th and 18th regenerated lenses taken from the experimental animals, there was no significant difference in morphology, histology, or expression of a panel of nine genes involved in lens development and differentiation. Tsonis says he was “astonished” by this result. Also, none of the lenses showed any sign of cataracts, an age-related defect. And over the entire 16-year experiment, it took an individual newt the same amount of time—about five months—to grow a new full-sized lens after removal of the old one. So not only were older newts able to regenerate perfectly normal, functional lenses, but the speed with which they regenerated was not affected by age or number of previous regenerations. “Everybody would have expected the opposite,” says Malcolm Maden at the University of Florida. “You expect to be less efficient as you age.”

Why do newts seem to defy aging, unlike humans, whose healing powers wane as they grow older? “I cannot answer it right now, but it’s a very interesting question,” Tsonis says. He might be able to gain clues by analyzing RNA samples from the lenses he and Eguchi extracted over the years. Tsonis says he plans on looking at how DNA repair enzymes, including telomerase, and other age-related genes are expressed in the aging newt’s lens, and testing DNA from the lens samples to see if there is any change with age in the length of telomeres, which get shorter with each cell division in mammals. Maden would also like to see if telomere length changes in other tissues and organs of aging newts, because it’s not known if the phenomenon occurs in amphibians.

Whether understanding regeneration in newts will have any impact on human lifespan is an open question. Tsonis says that one day scientists will elucidate the molecular mechanisms behind regeneration, and the “good news” from the newt study is that once we fully understand it, “age will not be a problem” in terms of, for example, wound repair. After all, he says, “old people need regeneration, not young ones.”

A Hidden Jewel refers to an article, published in a specialist journal, which has been evaluated in Faculty of 1000, a post-publication peer review service of the Science Navigation Group. Read the evaluation of Eguchi’s article.

See the full slideshow.[gallery]

Interested in reading more?