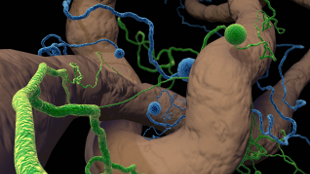

Close-up of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi connecting roots of plant hostsIMAGE COURTESY OF YOSHIHIRO KOBAE

Close-up of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi connecting roots of plant hostsIMAGE COURTESY OF YOSHIHIRO KOBAE

Nutrient exchanges between plant and fungal symbionts are relatively fair, with partners that provide the most resources being rewarded with more nutrients in return. The findings, published this week in Science, point to a reciprocity in mycorrhizal interactions uncommon among this type of symbiosis.

The study suggests “that control in this mutualism is reciprocal,” Alastair Fitter, a professor at the University of York who did not participate in this research, told The Scientist in an email, and “that the widely accepted view that the plant controls the symbiosis is wrong.”

Mycorrhizae are mutualistic associations between plants and fungi, in which plants trade carbohydrates for nutrients, such as phosphorous and ntrogen, and other benefits provided by the fungi. As the researchers point out in their study, mycorrhizae are “arguably the world's most prevalent mutualism,”...

Heike Bücking, a professor at South Dakota State University, and her team grew the legume Medicago truncatula with three species of mycorrhizal fungi that contribute different levels of phosphorous to the plant. Over the span of a day, the researchers saw that the most generous species received the highest levels of carbon in return, suggesting the plants somehow monitor their nutrient intake and reward their fungal partners accordingly.

In another experiment, the researchers grew carrot roots with a single fungal species, but supplemented the petri dish with different levels of phosphorous. In this case, the same balance developed: those fungi with the most phosphorous to give received the most carbon in return.

“This is the first time this has been shown—that a host plant is able to transfer more or less carbon to different fungi and thereby reward good fungal behavior or punish those mycorrhizal fungi that cheat,” Bücking said.

And the same held true for the fungi—they were able to monitor the contributions of the plants and adjust their returns to match. Bücking and her colleagues grew one fungus in a dish with two sets of roots—one with a higher level of carbon available, and one with a lower level of carbon. The fungus provided more phosphorous to the root that had more carbon to trade.

Paola Bonfante at the University of Torino, who was not involved in this study, said the findings are valuable to the understanding of symbiosis between plants and mycorrhizal fungi, but there are more factors than just carbon and phosphorous availability that might influence the way partners trade resources. For example, a fungus might be a generous nitrogen provider or might improve the soil conditions for the plant. “Therefore we can hypothesize that the plants reward changes depending on the environmental situation,” Bonfante wrote in an email.

Bücking said her group is starting experiments on nitrogen transport to see if similar mechanisms are at work there as well.

Correction: This story has been updated from its original version to correctly indicate that the experiment involving variable levels of phosphorus was conducted with carrot roots, not a legume. The Scientist regrets the error.

E.T. Kiers, et al., “Reciprocal rewards stabilize cooperation in the mycorrhizal symbiosis,” Science, doi:10.1126/science.1208473, 2011.